Southern Gothic

TRES MALL

Derek G. Larson

In the fourth episode of Très Mall, “Southern Gothic,” psychological, economic, technological, mediatic, and ethical concerns converge into a dissociative web, unsettling the integrity of the subjectivities of people, cartoon characters, non-human animals, objects, and devices.

Très Mall’s—that is, the mall’s—bespectacled welcome sign welcomes us with a discourse on gentrification, given by urban theorist Richard Florida, who talks of the twisted theory of benign neglect, letting New York crumble so it became cheap and rebuildable for the wealthier. This didn’t happen, or not entirely, but now, we are so familiar with the idea of “gentrifiers” and the role that creative people looking for cheap places have in changing neighborhoods that Jon is nodding off.

In this twisted version of "A Christmas Carol", after dozing off, Jon finds himself visited by an animated (in the many senses of that word) version of Nietzche’s The Birth of Tragedy voiced by philosopher Babette Babich. The book/Babich tries to get at the core of Jon’s dreams, but not so much evasive as unfocused, Jon can’t seem to answer her questions and asks his own instead: what happens in the minds of an animal? Do they know the violence they are capable of? Do they have a true sense of morality? Do we?

Do we need another remake of Stargate, again? Yet another question we have to ask ourselves in this nostalgic era of reboots amid the flatness of the internet’s non-time. Charlie Chaplin can live forever in our present on YouTube; all screens show light that’s already happened.

Although Jon and his friends may seem disaffected, squatters driven less by political motivations and more financial limitations, journalist Eileen Traux—a duck dropped from a ceiling—has hope for millennials and their younger Gen Z brethren and their social conscious, sense of connectivity, and borderless aspirations. And of course, Jon may be lethargic, but not unconcerned: with Oreos and thumbtacks he lectures on the vastness of time, but still, it’s not a positive proposition: humans love killing whatever’s new. We could wonder at the internal thoughts of aliens, or we could just colonize their world.

And what violence does the screen inflict? Figures can be disappeared with a single click. Cartoons and violence—human and animal—have long gone hand in hand, just watch Looney Toons. In cartoons, unwanted guests who just “show up” can be quickly disappeared with an off-screen cane.

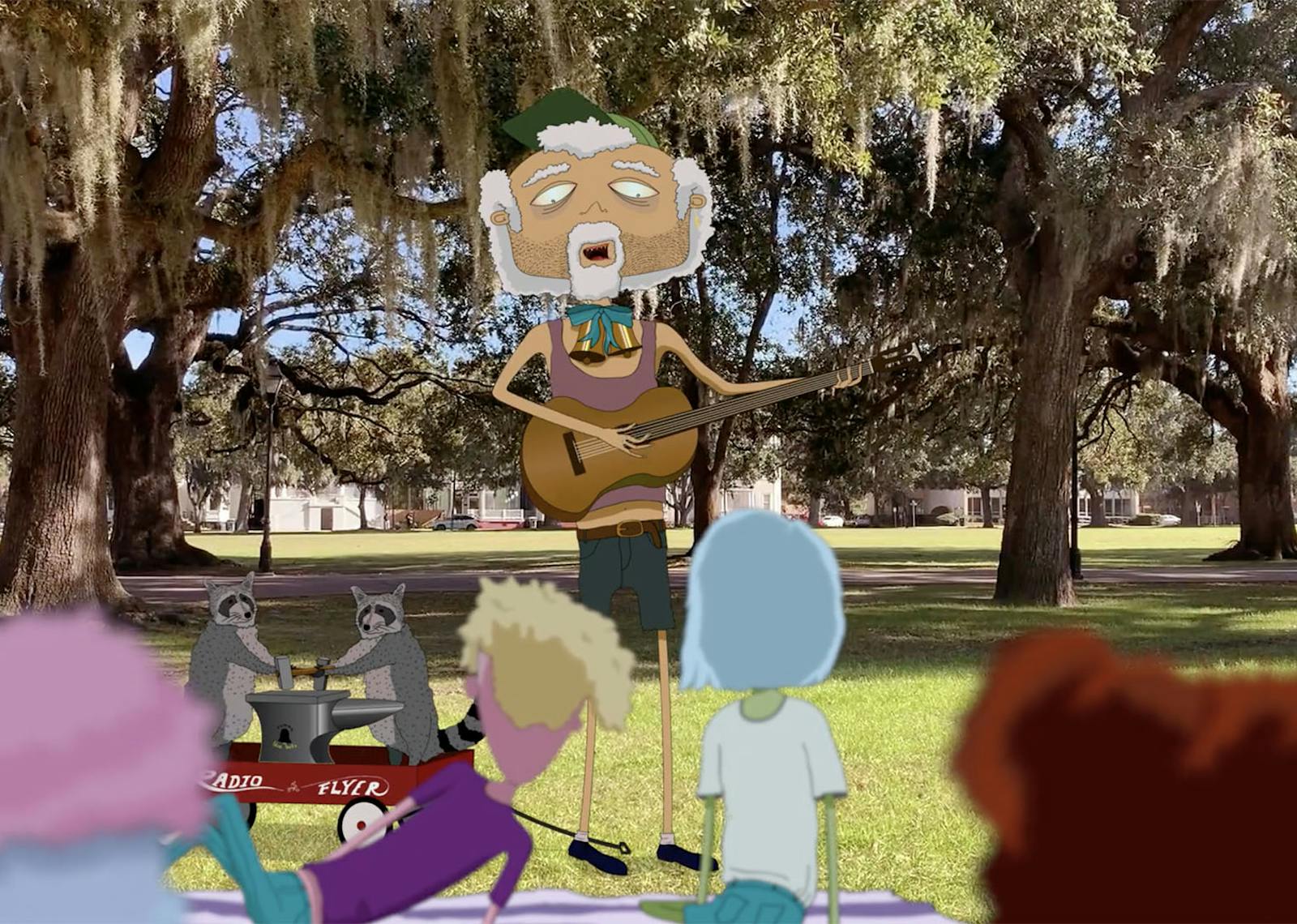

The problem of other minds, animal, animated, or human, a question that’s vexed philosophers for time immemorial, becomes even murkier in a time when so many purported people we communicate with aren’t visible. Could it just be a robot at the other end of a phone call, a character on a park bench wonders aloud into his phone and to the “real” human being by his side.

So much of the present is encounters with the past. Remakes and nostalgia, yes, but also ideas, artifacts, a box of hairbrushes references to a Brian Jonestown Massacre song. So often these signs and objects mean, in and of themselves, nothing; and yet humans—IRL and cartoon alike—desperately wish to put meaning to them. In the case of Southern Gothic, this means believing that the encounter with these objects indicates someone leaving them for them, convening the very moment they occupy together. There is no agency, then, and yet so much interpretation, so much not just self-possession, but self-obsession.

We return to the mall, and to Florida who now welcomes us into it, who muses on the embarrassment of Donald Trump, unmaking America again—another reboot, again. But who asked for America to be made? Not those who had made it first, before “America” entered the consciousness it all. In a time of reboots and robots, the only easy way to cling to faith is believing you always know what’s next: what’s happened before.